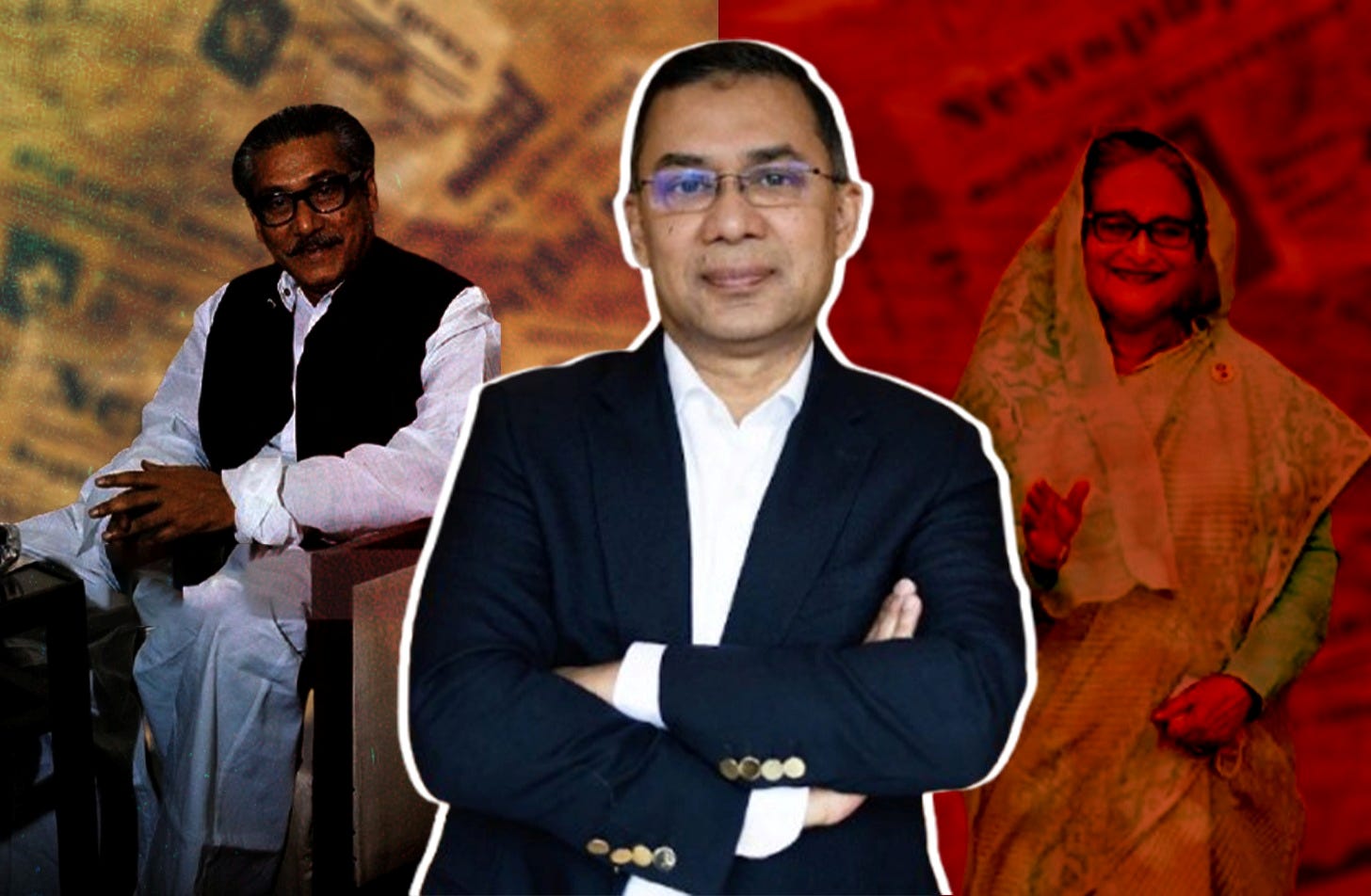

Tarique Rahman and Media Flattery Making Power Untouchable

Bangladeshi media once softened Mujib and Hasina’s power with undue praise. Now, similar flattery surrounds Tarique Rahman. If tough questions fade, democracy may slide again.

বাংলাদেশের গণমাধ্যম একসময় শেখ মুজিব ও শেখ হাসিনার বন্দনায় গণতন্ত্রকে দুর্বল করেছিল। আজ যখন তারেক রহমানকে দ্বিধাহীন প্রশংসায় ভাসানো হচ্ছে, তখন প্রশ্ন উঠছে- গণমাধ্যম কি আবারও সেই পুরোনো পথেই ফিরছে?

Democracy rests on a simple rule: those in power must be watched.

The media exists to do that watching. When journalists ask hard questions, leaders stay careful. They review their actions, correct mistakes, and remain mindful of public anger.

However, when the media turns into a cheering squad, something breaks. Leaders stop listening. They begin to believe they are untouchable. Slowly, democracy turns into a show. Bangladesh has seen this before.

At different moments, sections of the media shielded the rule of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and later Sheikh Hasina. Too often, praise was louder than truth. Now, as the political landscape shifts again, a new question is resurfacing public conversations: Is the media repeating the same mistake with BNP chairman Tarique Rahman?

In recent months, many media outlets have rushed to wrap him in heroic language. He has been likened to “Banglar Martin Luther King.” Several media voices sound less like watchdogs and more like campaigners. Instead of pressing him on what kind of democracy he would build, much of the coverage leans towards admiration.

This is not a minor concern. This is often how democracies begin to collapse.

This article looks at how media flattery weakened democracy in the past, and why the same pattern risks returning today.

Media During the Sheikh Mujib Era

In 1975, press freedom in Bangladesh sharply declined during Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s rule. Sheikh Mujib, the country’s first President and Prime Minister and a key figure in independence, banned all newspapers except four state-approved outlets: Dainik Bangla, Bangladesh Times, Ittefaq, and Bangladesh Observer.

This decision severely limited press freedom. Praise replaced truth. The media helped build a personality cult and supported a one-party system instead of questioning power. Later, in 1977, President Ziaur Rahman lifted the media ban to restore democratic practices. Decades later, Sheikh Hasina followed a different but equally effective path to control the media.

Media Role During the Sheikh Hasina Era

Sheikh Hasina, Sheikh Mujib’s daughter, expanded media control using state power during her rule until she was removed by a student-led movement in August 2024. Instead of banning media only, her government used ownership pressure, controlled advertising funds, intelligence agencies like the DGFI, and harsh laws such as the Digital Security Act (DSA).

Several media outlets were shut down during her tenure, including Dainik Dinkal, Dainik Amardesh, Diganta Television, Islamic TV, and Channel 1. At least 255 journalists faced legal cases under the DSA. These actions created fear and led to widespread self-censorship.

Many media outlets turned into government mouthpieces. Prime Ministerial press conferences became platforms for praise, not accountability. In one example, when a journalist asked Sheikh Hasina about rising prices of essential goods, a senior journalist and former CEO of Ekattor TV Mozammel Haque Babu discouraged her from answering, calling it a “dusto prosno” (mischievous question).

During the 2024 student protests, some media repeated official claims and labeled protesters as criminals. Once again, the media protected power instead of the public. Instead of acting as the fourth pillar of democracy, the media became part of the state machinery.

After Sheikh Hasina’s removal, people expected stronger and more critical journalism. However, recent trends suggest the media may again be leaning toward a political force likely to win the February 12 national election.

Media Attitude Toward Tarique Rahman

After Sheikh Hasina fled to India in August 2024, Bangladesh entered a power vacuum. While certain institutions like universities and banks began to regain public trust, the politics itself became shaky; especially, the BNP politics felt directionless. Perhaps, Tarique Rahman’s return in December after 17 years in exile was highly acclaimed for that reason. The media followed the moment closely, but the coverage soon went beyond a homecoming.

Five days later, Khaleda Zia passed away. That ended the BNP’s old chapter. Tarique Rahman rose as party chairman and the BNP’s central power.

Of course the media will focus on him. He leads a major party and could shape the next government. But attention is not enough. Journalism has a duty to ask what his leadership would mean for democracy, good governance, and the rule of law.

His past still carries serious allegations linked to corruption during the BNP years from 2001 to 2006. The public deserves clear answers on how he will address that history and whether he will tolerate free, critical reporting. There is also the issue of party control. Intra-party clashes are common. At least 85 people were killed in internal feuds within the last year. His party also failed to stop rival candidates in at least 78 constituencies in the national election of 2026. If the chain of command breaks inside a party, how will it hold inside the state?

Yet much of the recent coverage avoids these questions. Many reports paint him as patient, heroic, and a future prime minister. This raises a blunt question: is the media watching power, or kneeling before it?

Some journalists felt uneasy and expressed concerns: senior media figures have returned to flattery for political benefits, while another warned online that too much praise can help build the next strongman, just like the last one. Even some journalists blatantly joined BNP’s media team for the upcoming election. With their loyalty and service to a political party, how can journalists maintain their professional integrity?

Media Responsibility and Public Expectations

This is where the real danger sits. In the past, media praise helped turn public hope into unchecked power. When journalists stop pushing back, history does not pause. It repeats.

Tarique Rahman faces hard tests: a free and fair election, an independent justice system, real action against corruption, respect for democratic norms, and stable foreign relations with countries such as India. He must also rebuild international trust and prove that his future leadership will not copy his past.

The media must test these promises, not broadcast them.

The lesson is simple. A free press must stay independent. Leaders must earn trust every day. Bangladesh does not need another savior. It needs balance.

Whether Tarique Rahman becomes a bridge to stronger democracy, or the start of another slide, depends not only on him. It also depends on whether the media remembers its duty: to serve the people, not power.

About the Authors

Jamal Uddin is the Editor-in-Chief of The Insighta and a Lecturer in the Department of Communication at Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. Former journalist from Bangladesh with research interests in media, health, and politics. He can be reached at jamalus2014@gmail.com

Shahedur Rahman is the Op-Ed-Editor of The Insighta and a media professional with over 17 years of experience in journalism and editing. He can be reached at rahmankazishahedur@gmail.com

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect The Insighta’s editorial stance. However, any errors in the stated facts or figures may be corrected if supported by verifiable evidence.

Strong piece on the cyclical danger of media sycophancy. The pattern from Mujib to Hasina repeating with Rahman is textbok - when journalists trade watchdog role for cheerleading, democracy erodes fast. The stat about 85 internal party deaths hints at something darker than the glowing profiles suggest. Media independence isnt just nice to have, its structural protection against autocracy.