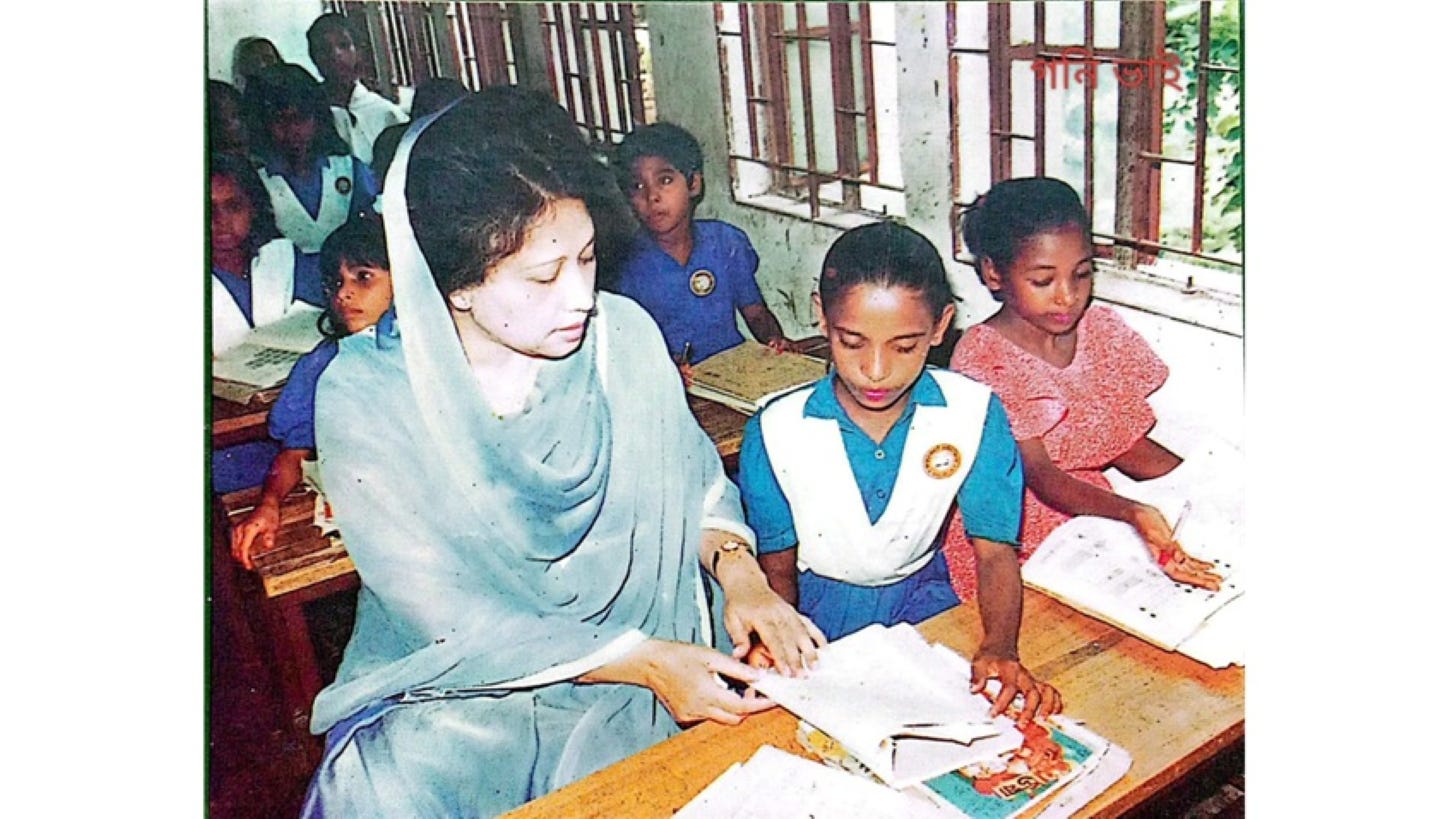

Khaleda Zia, the Forgotten Pioneer Behind the Transformation of Women’s Education in Bangladesh

Khaleda Zia’s girls’ stipend program revolutionized Bangladesh, raising education and jobs for women, reshaping social norms, and empowering a generation that drove historic political participation.

একটি নীতিগত সিদ্ধান্ত কীভাবে বদলে দিতে পারে একটি জাতির ভবিষ্যৎ? বেগম খালেদা জিয়ার নেয়া মেয়েদের শিক্ষাবৃত্তি কর্মসূচি শিক্ষা, স্বাস্থ্য ও রাজনীতিতে নারীর উত্থান ঘটায়। সেই প্রজন্মই পরে স্বৈরাচারবিরোধী ঐতিহাসিক আন্দোলনে গুরুত্বপূর্ণ ভূমিকা রাখে।

In the early 1990s, fewer than 20 percent of girls eligible for secondary school were actually enrolled, and in rural areas the number was even lower. It was during this time, under the leadership of Prime Minister Khaleda Zia (1991–1995), that a transformative and nationwide secondary school stipend program for girls was introduced, a policy that would go on to reshape the country’s social, educational, and economic landscape.

By 1995, the enrollment of girls in secondary education had jumped to around 45 percent. The impact was both immediate and enduring. In a study I conducted in 2014–15, I found that in many areas, girls’ enrollment in schools had surpassed that of boys. But the effects of this initiative extended far beyond classroom walls. Numerous studies have since shown that the program not only increased girls’ enrollment in the short term but also led to long-term improvements in women’s higher education participation, delayed marriage age, better maternal and child health outcomes, lower child mortality, and enhanced female employment. Domestic violence rates declined, and intergenerational effects were evident in improved educational and health indicators among the children of those first stipend recipients.

The stipend program triggered a cultural shift. Even conservative families who were initially reluctant to send girls to school, whether for modesty, cost, or custom, began to embrace education. Some may have done so initially for the modest stipend, but their daughters went on to become graduates, professionals, and leaders. Girls who once couldn’t step beyond the courtyard now study at universities. In the 1990s, women accounted for less than 5 percent of physicians in Bangladesh; today, the figure exceeds 30 percent. Back in 2015, even in many remote areas, women were still unable to seek medical care due to the lack of female doctors. That landscape has changed because of one policy choice.

This education revolution also sowed the seeds for something more radical: women’s political participation. In 2024, we witnessed a historic wave of women-led resistance against fascism and autocracy. The scale and strength of women’s mobilization in Bangladesh had no precedent in South Asia. While this uprising had many contributing factors, it is difficult to imagine such a movement without the decades-long investment in girls’ education that empowered a generation of women.

Bangladesh’s stipend program for secondary school girls was pioneering. It became a model emulated by countries like India and Pakistan. Research across the world has confirmed that women’s political participation positively influences governance and social outcomes. Bangladesh lived that truth. But it also revealed the opposite: South Asia’s first female authoritarian ruler, Sheikh Hasina, who presided over mass repression, electoral manipulation, and systematic abuse. Her regime produced women thugs like Papiya, weaponized the state against dissenters, and in the end, she fled in disgrace, making her the only South Asian woman dictator forced into exile. But that’s another story.

The point is this: Khaleda Zia, Bangladesh’s first female prime minister, made an enormous contribution to women’s empowerment through policy. And yet, because she challenged Indian hegemony in regional politics, many self-proclaimed feminists have vilified her as “anti-women.” This historical distortion is not only unjust, but also dangerous.

Over the past fifteen years of fascist rule, Khaleda Zia has suffered immense persecution. She was forcibly evicted from her home, denied medical care, imprisoned on fabricated charges, and separated from her children. Her experience as a political prisoner during 1971 was mocked by those who trade in the business of “war heroine” politics. Meanwhile, the looters of billions used a minor corruption allegation involving a few million takas to drag her through the mud. And yet, through it all, she stood tall and said: “I have no home abroad. I will never leave this country. If I must die, I will die here.”

Let us also remember her political integrity. In 1996, she held a one-sided election with 21% voter turnout but stepped down within three weeks in response to public demand. Compare that with the shamelessness of those who clung to power for years through 5% turnouts, midnight ballots, and 153 uncontested seats.

Khaleda Zia made mistakes, but she corrected them. She never refused to listen to the people. And when many fell for the euphoria of Shahbagh in 2013, it was she, and the visionary journalist Mahmudur Rahman, who warned of the fascist tendencies brewing within. She called out mob politics and judicial manipulation when others cheered them on. History has proven her right.

It was so soothing to see that she had been freed, acquitted in her cases, reunited with her family, and received with respect by the nation after the July revolution. It felt like a moment of poetic justice. Perhaps God has kept her alive to witness the fall of fascism and the rise of a hopeful, united Bangladesh.

After decades of struggle and sacrifice, she left us having seen a better Bangladesh.

About The Author

Dr. Sibbir Ahmad is a development economist. He can be reached at sibbirahmad520@gmail.com

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect The Insighta’s editorial stance. However, any errors in the stated facts or figures may be corrected if supported by verifiable evidence.