Development or Deception? The Myth of Progress Under the Fallen Hasina Regime

For over a decade, Hasina’s regime boasted grand infrastructure projects while curbing freedoms, crushing dissent, and sinking Bangladesh into debt. But was this real progress or a grand deception?

ক্ষমতাচ্যুত শেখ হাসিনা সরকার একদিকে দেশবাসী ও বহির্বিশ্বকে উন্নয়নের বর্ণিল গল্প শুনিয়েছে। অন্যদিকে কঠোর দমন-পীড়নও চালিয়েছে। বিরোধী কণ্ঠ রুদ্ধ করেছে। দেশকে বিপুল ঋণের বোঝায় জর্জরিত করেছে। প্রকৃত উন্নয়ন তবে কোনটি? অবকাঠামো ও বৈষয়িক উন্নয়ন? নাকি মানবিক স্বাধীনতা? এই নিবন্ধে হাসিনা সরকারের তথাকথিত উন্নয়নের আড়ালে লুকিয়ে থাকা নির্মম বাস্তবতার প্রতি আলোকপাত করা হয়েছে।

Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen defines development as “freedom.” He challenges the dominant view of development that is mistaken for mere material progress. Sen thinks that true human development goes beyond economic gains. He insists that actual development is not just about access to assets and resources but about people’s ability to meaningfully use them and benefit from them. Sen’s view of progress reveals why Sheikh Hasina’s so-called “mega” development projects failed to deliver lasting change in the lives of ordinary Bangladeshis. In this article, I put the regime’s development narrative to the test through Amartya Sen’s idea of freedom, later refined as “freedoms.” Indeed, without fundamental freedoms, development becomes a deception that denies people real progress.

Failed to render LaTeX expression — no expression found

Amartya Sen’s Vision of Progress vs. Hasina’s Reality

Sen’s idea of development as freedom is worth elaborating. He opposes the traditional view of development as increasing material benefit and happiness, because mere access to those utilities does not guarantee well-being. Some individuals with limited economic resources look happy and content, while others with great wealth remain unhappy. This makes material benefit or “happiness” not a reliable indicator of public well-being. Sen believes that the quality of life, if measured this way, would be flawed and misleading. Instead, he urges us to look at what people actually are “able to be” (being) and “able to do” (doing). In another word, Sen asks what conditions or states people are currently in—like “being safe,” “being healthy”—and what choices people are able to make—like having a good job and feeling valued. Sen calls these beings and doings as human capabilities, or true functionings, because they reflect people’s actual conditions in society. Putting this lens in the context of Bangladesh, we must ask: During Sheikh Hasina’s 16-year autocratic rule, what life conditions did the ordinary Bangladeshis live in? What meaningful actions or activities were they able to take to achieve the kind of life they genuinely valued or had good reasons to value?

Mega Projects or Mega Illusion?

This is not merely about the amount of material goods or infrastructure that Sheikh Hasina expanded, but about the notable strides in large-scale projects that her regime made–at least, that is what anyone might believe when coming across her widely circulated development narrative—The country is floating in prosperity. Ambitious projects such as the Padma Bridge ($3.87 billion), Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant ($12.65 billion), Dhaka Metro Rail ($2.74 billion), Elevated Expressway ($1.1 billion), and the much-publicized Digital Bangladesh initiative ($5.4 billion) could appear impressive at first glance, but the critical question remains: what actual improvements did these mega projects bring to the everyday lives of Bangladeshi citizens? What were their real living conditions? How much freedom did they have to build their own futures? These questions are essential for not only evaluating Hasina’s rule but also guiding future governments and policymakers toward meaningful development.

If these billion-dollar projects truly enhanced social wellbeing, why did people take to the streets, risking their lives to protest the regime? Why were over 1,500 students and ordinary people killed while standing against the authoritarian reign? Answering these questions is complex, but three key realities emerge—Hasina’s development model was marred by corruption, burdened by persisting debt, and sustained through autocratic control.

Who Truly Benefited?

First, Hasina’s mega development projects came with mega corruption, primarily benefiting her party loyalists, business elites, government employees, and law enforcement agencies and military—all played a role in safeguarding her regime. Reports of large-scale corruption have been widely documented by international agencies and media. Between 2009 and 2023, Bangladesh lost an average of $16 billion per year to illicit financial outflows—more than twice the total received from foreign aid and direct investments. During the same period, Bangladeshi households paid an estimated BDT 146,252 crore ($12 billion) in bribes or unofficial fees to access services across 18 sectors and institutions in the country.

A Nation Drowning in Debt and Deception

Second, Hasina skillfully manipulated public perception with the help of complicit media, creating the illusion that her ambitious projects were a gift to the nation. This narrative largely evaded public scrutiny as mainstream media failed to question the financial management of these projects. It is now evident that most of the funding came from foreign loans. According to a Dhaka Tribune report (September 19, 2024), by June 2024, Bangladesh’s foreign debt had skyrocketed from $23.5 billion in 2009—when Hasina took office—to $103.78 billion. This staggering 341% increase in debt translates to over $80 billion in new foreign loans, including $71 billion borrowed directly by the government. The details are even more alarming: between June 2020 and June 2023, foreign debt surged by 51%—begging a question: where did this money go?

Third, these mega projects—and the mega loans that funded them—raise a fundamental question: Who truly benefited from them? Clearly they are not the public. Ordinary citizens were almost entirely excluded from the development process, having no say in planning, implementation, or oversight. From local government bodies to the national parliament, public voices were systematically silenced and their basic rights were denied. Meanwhile, elections were reduced to mere formalities, with opposition parties crippled by mass arrests, enforced disappearances, and media censorship. Development became a tool for consolidating power rather than improving lives. So, in reality, does such development reflect true prosperity and progress, or was it just a façade of economic growth masking an increasingly entrenched autocracy?

Amartya Sen’s concept of development aptly explains Bangladesh’s development trajectory. Between material goods and their intended benefits, Sen identifies that human capabilities (or functionings) are often missing, leading to deprivations (or unfreedoms) in society. True development, according to Sen, is not merely about acquiring assets and wealth but about expanding people’s choices and freedoms. Without the ability to be and do, material goods alone make little or no difference beyond providing temporary delight or comfort.

Sen makes this idea clear with the example of a standard bicycle. While a bike is generally seen as a means of transportation, whether it actually serves this function depends on various personal and societal conditions. A person may feel momentary happiness in owning a bike, but real satisfaction comes from its actual use and the benefits it provides. Now, consider the barriers: What if the bike owner doesn’t know how to ride? What if they fear heavy traffic? What if there are no bike paths? What if they don’t have one leg or are physically unable to cycle? A simplistic, utility-based development policy tends to overlook these crucial factors—capabilities and freedoms—that determine whether the bike can truly give transportation. For Sen, real development means addressing these constraints: building bike paths, managing traffic well, and designing adaptive tools for individuals with disabilities, so that everyone can genuinely benefit from the resource.

Digital Bangladesh—A Grand Promise Without Public

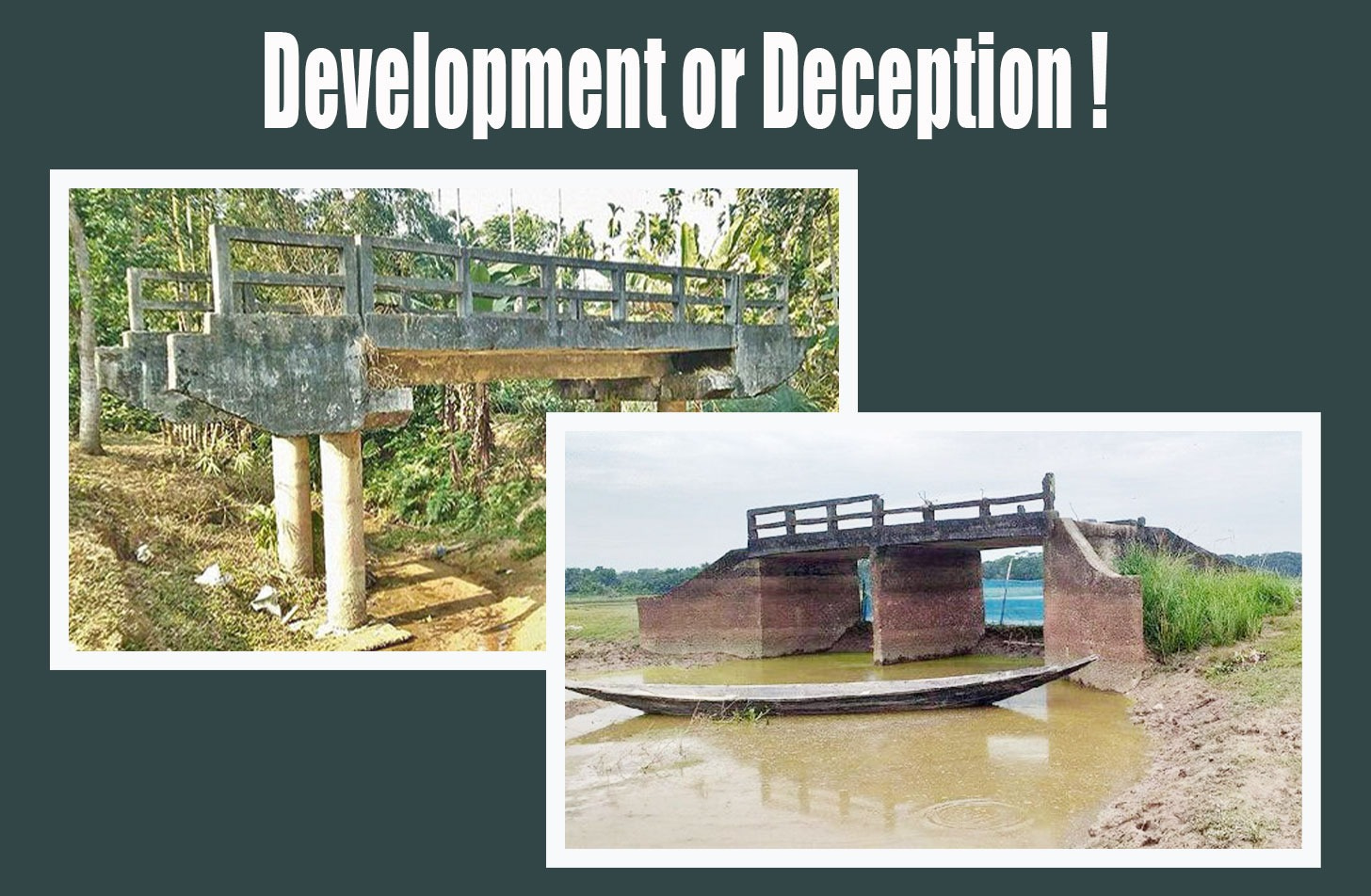

Let’s put Amartya Sen’s idea of functionings or capabilities into the perspective of the so-called development initiatives under Sheikh Hasina’s regime. We find too many instances where infrastructure was built but remained nearly unused—failing to generate any desired utility. For example, multiple reports published in mainstream media have shown images of bridges and culverts standing in the middle of open fields. They are disconnected from any roads and hence are completely useless. A similar pattern emerges with the much-publicized Digital Bangladesh initiative. The government claimed its goal was to bring public services to citizens' doorsteps, yet the entire digital infrastructure was designed around government officials, agencies, and select entities like NGOs—without meaningful public participation. From planning and implementation to evaluation, the public was systematically excluded from the process. Instead, this digitalization program became a conduit for siphoning public funds.

This is not to say that infrastructural development—whether bridges or digital platforms—is inherently useless. Rather, quite the opposite: a bridge or culvert can greatly improve people's lives if properly connected to roads and transportation networks. Likewise, government websites and digital services could be genuinely transformative if the public had active participation and ownership in those services and voices in shaping their needs. But without active engagement, billions were either wasted or severely underutilized.

The Vanishing Right to Political Participation

Now, let’s turn to political developments over the past 16 years under Sheikh Hasina’s regime. Take elections, for instance—Bangladeshi citizens once had the luxury of exercising their power by casting votes in every election cycle. Historically, concerns over electoral fairness and neutrality existed, yet people could still participate, even in flawed elections. However, under Hasina’s rule, that luxury was entirely stripped away. While her government maintained the election cycles—primarily to showcase legitimacy to the world, the entire election process was controlled. The regime systematically dismantled political opposition, barring major parties from routine political activities. Senior leaders and hundreds of thousands of activists were imprisoned, while thousands were forcibly disappeared. In some elections, even independent candidates were absent, as fear silenced nearly all dissent. At polling centers, ruling party operatives brazenly seized ballots from voters, often aided by law enforcement. Meanwhile, media complicity further deepened the crisis, shielding these electoral manipulations from critical scrutiny. Elections could have marked a milestone in Bangladesh’s political progress—had the Awami League not hijacked the process for its own consolidation of power.

Similarly, the voices of ordinary citizens, students, teachers, journalists, photojournalists, and social activists—except for those loyal to the regime—were systematically silenced. Even a simple social media post, reaction (like and love), or comment could lead to lawsuits, arrests, and/or imprisonment. The entire country was gripped by fear. Those who dared to raise their voices—whether online or in the streets—faced brutal retaliation and state-sponsored harassment. The repression extended beyond borders; critics living overseas saw their family members back home detained, interrogated, and/or tortured.

Meanwhile, nearly every social, educational, and public institution was eroded through rampant politicization and corruption. Schools, colleges, universities—and even religious institutions such as mosques and Madrasahs—fell under the grip of the regime’s loyalists. Administrative appointments and operational decisions were dictated by political allegiance rather than merit. Everyday citizens had to seek approval from ruling party operatives for even basic transactions. From Amartya Sen’s perspective, while resources and infrastructure existed—albeit financed through astronomical foreign debt and tainted by corruption—there were no meaningful functionings that allowed people to be or do what they valued. The fundamental freedoms required for true human development were extinguished.

With all this in mind, we must ask: What does true development look like? Is it measured by highways, bridges, and skyscrapers, or by freedoms and opportunities that allow people to live with dignity? Can a nation be considered developed when its citizens live in fear—unable to speak, act, or dream? And most importantly, can economic progress be sustainable when built on the foundations of repression, corruption, and debt? The answers to these questions will not only challenge the very definition of development itself but also serve as a reminder for future leaders to prioritize people-centered progress.

About the Author:

Mohammad Ala-Uddin, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at Saint Mary’s College, Notre Dame, Indiana, USA. A former journalist and NORAD Fellow, Dr. Ala-Uddin specializes in global communication, digital media technology, and sustainable social change. He can be reached at alauddinm26@gmail.com

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the authors' own and do not necessarily reflect The Insighta's editorial stance. However, any errors in the stated facts or figures may be corrected if supported by verifiable evidence.