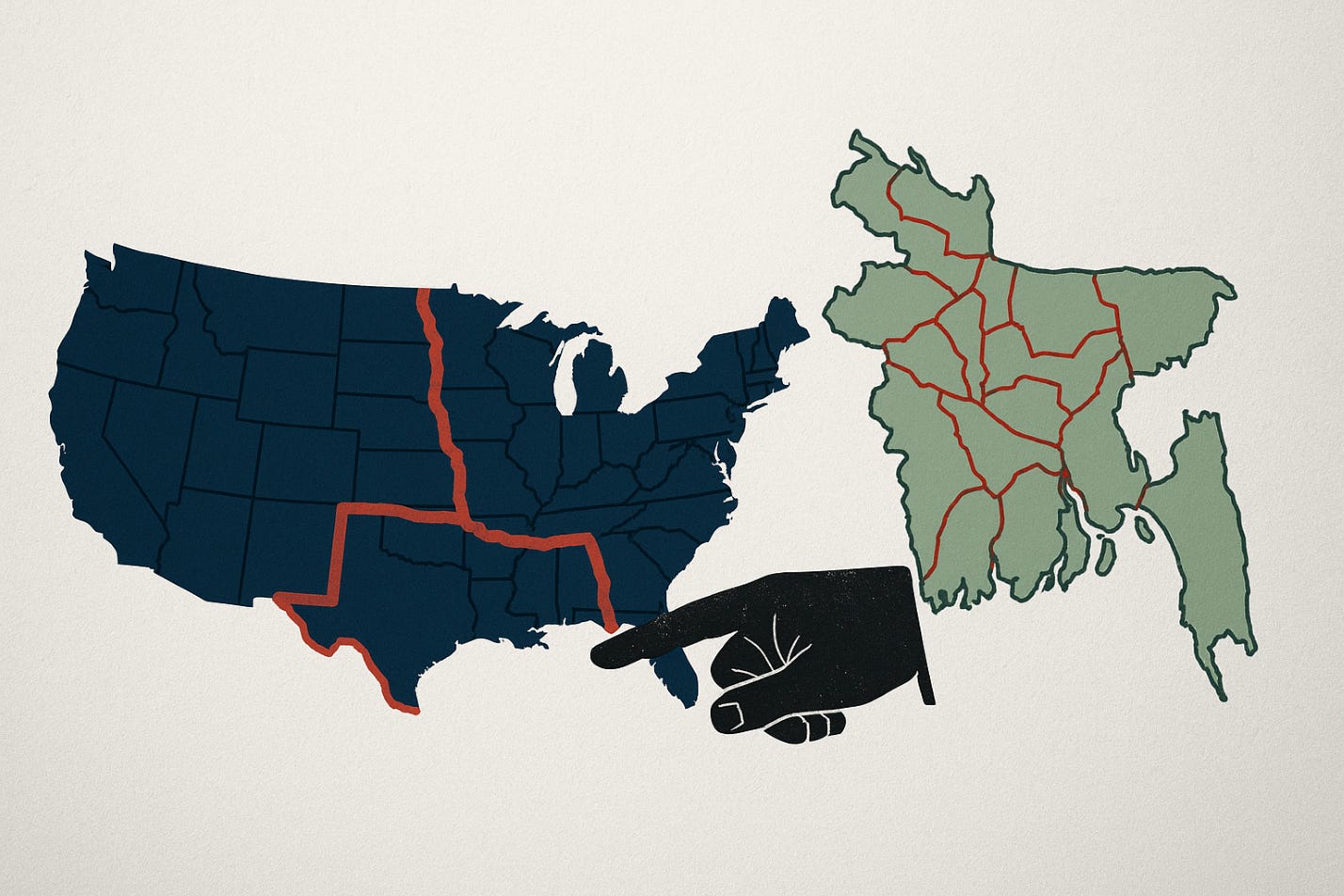

What the U.S. Gerrymandering Debate Can Teach Bangladesh about Fair Political Representation and Democratic Accountability

When power redraws borders, democracy bends. This piece explores how the U.S. case Shaw v. Reno redefined racial gerrymandering, and what Bangladesh’s boundary politics can learn from it.

গণতন্ত্রে সঠিক প্রতিনিধিত্বের ভিত্তি নির্বাচনী এলাকার ন্যায্য সীমানা নির্ধারণ। তবে ক্ষমতাসীনরা যখন নিজেদের সুবিধামাফিক মানচিত্র আঁকে, তখন জনগণ তাদের শক্তিশালী অবস্থান হারায়। যুক্তরাষ্ট্রের Shaw v. Reno রায় জাতিগত গেরিম্যান্ডারিংয়ের সীমা টেনেছিল। বাংলাদেশের রাজনৈতিক সীমানা এবং রাজনীতির জন্যও এতে আছে গুরুত্বপূর্ণ শিক্ষা।

Fair representation is one of the most important parts of a democracy. But when voting areas are drawn to favor those in power, some communities lose their voice and elections lose their fairness. This unfair practice is called gerrymandering. It happens when the borders of voting districts are changed to give one political party an advantage (partisan gerrymandering) or to weaken the voting power of certain ethnic or language groups (racial gerrymandering).

In recent years, Bangladesh has faced concerns about gerrymandering. Political influence over how voting areas are drawn has raised questions about whether every citizen’s vote truly counts. The United States has also faced this problem, especially when race plays a role in shaping voting districts. A major Supreme Court case in 1993, Shaw v. Reno, set new limits on how far governments can go in drawing districts that affect minority voters. This case became a key moment in defining fairness and equality in U.S. elections.

By looking at how the U.S. Supreme Court handled Shaw v. Reno, this article explores what Bangladesh can learn from the case to build a fairer election system, one where every person’s vote has equal value.

Case Summary of Shaw v. Reno

After the 1990 Census, North Carolina gained an additional congressional seat, bringing its total to twelve, and needed to redraw its election map. To ensure voters’ protection against racial discrimination in voting processes under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the state created two Black-majority districts for adequate representation of Black voters. However, one of these districts, District 12, was extremely asymmetrical in shape. It stretched over 160 miles, weaved through various counties, and was sometimes as narrow as a single highway lane. Five white residents of North Carolina challenged the constitutionality of the revised redistricting plan, claiming it violated their Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause rights through racial gerrymandering.

The case reached the US Supreme Court, which faced a difficult question: whether a state can draw district lines to help minority voters without crossing the line into racial segregation? In a close 5–4 decision, the Court didn’t strike the district down immediately, but it did say the challengers had a valid claim. The district’s bizarre shape strongly suggested race was the primary reason for its design, which raised serious constitutional concerns. The majority opinion, delivered by Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, reasoned that North Carolina’s districting plan was so extreme in its racial focus that it raised constitutional concerns over the equal protection clause. Justice O’Connor called the shape of the district “bizarre” and said that it bore an “uncomfortable resemblance to political apartheid” and explained that it could not stand because the redistricting had no purpose other than to separate voters by race.

The ruling emphasized that the state’s redistricting efforts, while perhaps well-intentioned in trying to secure minority representation, must also respect the constitutional limits regarding race-based classifications. Thus, the Court did not oppose the creation of majority-minority districts per se but underscored that race cannot be the predominant factor in redistricting and that there should be a compelling state interest.

Gerrymandering in Bangladesh?

The tension between fair representation and racial classification that Shaw v. Reno has exposed resonates beyond the United States. Although the concept of “Gerrymandering” is not so common in Bangladesh, there have been incidents of politically motivated gerrymandering in the past.

Ahead of the 2008 parliamentary elections in Bangladesh, the redistricting of 87 out of 300 constituencies serves as a perfect case of “gerrymandering,” where electoral boundaries were strategically altered to systematically favor the Awami League (AL) and weaken the BNP-Jamaat-e-Islami alliance, under the supervision of the so-called caretaker government (CTG) backed by the Bangladesh Army. Opposition voters were “packed” into a limited number of constituencies, concentrating their strength in a few seats while allowing AL to win surrounding constituencies with smaller, manageable margins. Strongholds of the opposition in urban and semi-urban areas such as Dhaka, Chattogram, and Khulna were “cracked,” dividing their voter base across multiple constituencies to dilute their influence and ensure AL candidates could win narrowly. At the same time, AL strongholds were combined with neutral or weak opposition areas to create “safe seats,” consolidating easy victories and minimizing the risk of losing in competitive regions. Boundaries in constituencies with previously narrow margins were subtly adjusted to tip the balance in AL’s favor, while the division and merging of opposition-heavy areas forced them to campaign inefficiently, straining resources.

Additionally, changes in voter rolls and constituency identification created confusion and potentially reduced opposition turnout, further benefiting AL. Overall, these manipulations, affecting almost 35% of the parliamentary seats, effectively engineered a parliamentary majority for AL without requiring proportional national vote support, leading to the systematic fall of the BNP-Jamaat alliance and illustrating a textbook case of election engineering under the influence of the then military-backed caretaker government. This engineered election ultimately pushed Bangladesh into a dark period marked by a significant erosion of democratic principles and civic freedom, and after 16 years of continuous struggle and popular movement, the Bangladeshi people were able to overthrow the Awami-Fascist government.

Although gerrymandering has remained a problem for US politics, the judgment of Shaw v. Reno has set some particular standards to be followed which I believe to be crucial for all nations including Bangladesh. By addressing the balance between minority representation and equal protection under the

law, Shaw v. Reno established a critical precedent for upholding electoral fairness and ensuring that districting plans adhere to constitutional standards.

In practice, the case made it much more challenging to create minority-majority districts that gave members of racial minority groups a greater political voice. Scholars argue that although Shaw v. Reno reduced the scope for crafting minority-majority districts, it simultaneously clarified constitutional boundaries so that measures intended to empower marginalized communities do not end up deepening racial separation. This underscores the case’s importance in navigating the complexities of racial representation in democratic systems

Opinion on the Court’s Decision

In my opinion, the Supreme Court’s decision in Shaw v. Reno was appropriately reasoned and constitutionally sound. The Court’s rigorous scrutiny standard correctly highlighted that race should not be the major criterion in redistricting unless it serves a compelling state interest, notwithstanding the district’s admirable goal. Thus, the decision emphasized that, in order to ensure electoral fairness, minority representation must be carefully balanced without jeopardizing the larger constitutional guarantee of equal protection.

Most legal experts agree that the decision is crucial for setting judicial limits on racial gerrymandering. One political scientist said the ruling prevented racial political polarization and gave much-needed clarity on the boundaries of acceptable racial districting. This viewpoint supports the Court’s conclusion that giving race priority when making districting decisions runs the risk of establishing polarizing “political apartheid”. Another legal scholar contends that by enforcing a high standard for race-based districting, Shaw v. Reno helped ensure that policies aimed at remedying racial inequalities remain constitutionally justifiable and narrowly focused.

What Bangladesh Can Learn from the Case

If a case resembling Shaw v. Reno were to arise in Bangladesh, the outcome might diverge significantly due to socio-political and legal differences. Bangladesh does not have a history of race-based districting, and although ethnic and linguistic minorities are acknowledged, party affiliation and ideological differences are more prominent in Bangladeshi politics than racial or ethnic districting.

How Bangladesh’s court might respond:

However, because the constitutional framework does not require thorough scrutiny for matters involving racial or ethnic considerations, the Bangladeshi judiciary does not follow the “strict scrutiny” standard set by the US court in Shaw v. Reno. Despite being grounded in principles of equality, Bangladesh’s Constitution generally affords the government wide discretionary powers to ensure social welfare, including the ability to divide the country into districts based on population or social purposes without necessarily subjecting them to strict judicial review. In practice, this means that the Bangladeshi judiciary might prioritize government intent, such as promoting equitable representation or social unity over strict adherence to anti-discrimination principles.

Social Context

Bangladesh’s society is ethnically diverse, but political issues typically revolve around economic and ideological divides rather than ethnic or racial conflicts, and political affiliations tend to drive electoral dynamics more than race or ethnicity. Therefore, if a district were drawn to enhance minority representation– such as for indigenous groups in the Chattogram Hill Tracts or linguistic minorities in northern Bangladesh– it might be viewed by both the government and the public as a positive measure for inclusivity rather than as racial or ethnic gerrymandering.

This social perspective could lead to broad support for districting aimed at giving historically marginalized groups a voice, with fewer concerns about equal protection in the U.S. sense. However, given the lack of a strict scrutiny framework, this kind of districting might proceed without sufficient safeguards against arbitrary or overly political decisions, raising the risk of reinforcing divisions if the purpose shifts towards consolidating political power under the guise of inclusivity.

Politics and Power

In Bangladesh, electoral districting often reflects the influence of ruling political parties, with boundaries occasionally adjusted to consolidate support in particular regions, especially during some previous national elections. Should a case similar to Shaw v. Reno challenge the government’s districting decisions on ethnic grounds, the judiciary would likely assess whether the districting served an acceptable public interest rather than strictly applying an equal protection standard.

As such, a Bangladeshi court might uphold the government’s decision if it gave a justification for advancing representation for a marginalized group or ensuring political stability. A comparable ruling in Bangladesh might favor the government’s discretion, particularly if it purports to be in line with national unity objectives, in contrast to the United States, where Shaw v. Reno established a precedent against race-based districting.

About the Author:

Md Hossain Al Rashed Badol is a law student at the University of Arizona with a keen interest in constitutional law and electoral reform. He can be reached at rashedbadol@arizona.edu

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect The Insighta’s editorial stance. However, any errors in the stated facts or figures may be corrected if supported by verifiable evidence.